I'll admit something. I've never liked the portfolio system of grading. As it was explained to me, and as I've seen it implemented, students gathered their work throughout a grading period. At the end of it, they submitted a portfolio. In better systems, students would sit with teachers and explain each piece that was submitted. The teacher and student would talk about it, like an artist talking about his/her work. It sounds wonderful. In practice though, I never got it.

Two big issues. The first is that it seemed to represent what a student knew, not what they currently know. I'd have issues with someone's best work being done in October. Second, it didn't seem to guarantee any sustained performance. Throw enough crap at the wall, eventually something will stick (this blog is a good example of that).

Toss in the fact that almost nobody has time for the critical interview portion—unless it's a schoolwide thing like a student-led conference—and you have a system that's assessing Young MC on Bust a Move and not the rest of Stone Cold Rhymin'. Or only using Sixth Sense when considering M. Night Shyamalan for a lifetime achievement award for film making.

It wasn't until a few weeks ago I realized that I had been using a portfolio system. It was just weekly.1

I've already mentioned my students keep track of their quiz scores in a folder. In the prongs they keep the tracking sheets and any other thing I need them to keep handy, like their benchmark scores and their periodic table. On the left side pocket they just keep stuff. Usually current quizzes. I don't really look at that side. On the right side they put anything they definitely want me to look at. Usually these are the quizzes, worksheets, or whatever that they think represent their current best efforts.

Additionally, in their science notebooks, they're supposed to put a sticky note if they want to draw my attention to anything they think I should look at. In practice, I've been bad about keeping up with the sticky notes because I suck about going to office depot and they're champs at turning all my post-it notes into flip books. My students are pretty good at drawing my attention though, either by folding a corner or drawing pink glitter hearts that say LOOK HERE.

A more organized version of me would also have them occasionally write justifications for why they want me to look at each piece of work. Maybe that me will arrive next year. As I'm typing this, I'm realizing that simply writing the standard number on anything submitted would be a good start and is so obvious I feel dumb for not thinking about it sooner. Hooray for blogging!

I still look at other things. I think it's important to take a look at the whole game. But the thing that's always appealed to me about the portfolio system is having students self-select what he or she perceives as quality. Developing the skills of self-evaluation is probably the most important thing I want a student to get out of standards-based grading.

1: And by weekly I mean, 3 out of every 5 weeks when none of my children are sick.

Showing posts with label implementation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label implementation. Show all posts

Monday, December 13, 2010

Sunday, August 8, 2010

SBG Implementation: Power User Tips

School starts in a couple weeks and right now I'm wrestling with interim (benchmark) assessments. I'll let you know how that works out later. Until then, I've noticed a bunch of bloggers have been hashing out their standards-based grading plans.

Here are some quick tips that really helped me in the setup phase.

Topics and scales:

Cut breadth, not depth. At some point you'll find you have a ton of standards to teach. You will then realize that you can't teach that many standards. It is really tempting to try to lower your expectations so you can cover all your standards. Don't. Cut the content. Never cut depth.

Take a whole bunch of those standards and put them into the "I'm just gonna mention these" pile. When I say mention, I don't actually mean, just-say-it-and-move-on. You can spend the whole day (or more than that if you want) in your preferred method of instruction.

Usually, that means I tell my kids that they're going to need these for the state tests, but it's not going to be important for my class. I'll spend a day here or there loading some vocab, boring them with a Powerpoint, or doing an isolated lab and then just move on.1 You could certainly skip it entirely, but I'd like to give them a sporting chance at guessing on a 4-option multiple choice test.

Anchor your scale with the hardest assessments/expectations on your students. It's not uncommon for your students to need to take a common department final, a state-mandated end of course test, and an AP or AP-like test. Choose the hardest one, analyze the depth, and use that as your anchor. I didn't buy into this one until very recently, but I believe it now. It's a real problem if I'm setting my criteria based on my district benchmark, which is asking kids to read a passage and summarize what happened. Meanwhile their state test is asking them to make inferences.

Ask to see other teacher's tests in other districts. One of the things that keeps me up at night is the depth issue. I really worry that I am setting my level of expectation at a 5, while schools in Cupertino, Palo Alto, and Los Altos (insert your local high SES cities here) are asking their students to perform at a 10. I emailed about 20 teachers in other districts for copies of finals, benchmarks, whatever. Six emailed back. Since then I've seen three or four more. Mainly I learned that most teachers just use the exams provided by textbooks, but it did help me adjust a few topics and I also saw some really cool problems.

Start with the 3: I'm putting this here because MizT mentioned she didn't really get this until she read this book. I know your scoring system might be different, but you've got to start with the goal. Whatever it is you want your kids to learn, start there. Then work backwards to build the learning progression, which turns into your scale. Take a full or a half step forward to extend your scale. If it looks like backwards planning, or UbD, it's because it is. If you're going to teach that way, you should assess that way too right?

Your scales and rubrics are actually kind of useless by themselves. Sorry. I know you worked really hard on them. Your standards are meaningless until you define them with assessments and exemplars. There's a good example of that here, but it's gated. No matter how detailed and well thought out your scales are, you and your kids aren't going to really get them until they see some exemplars or they know how they'll be assessed. So don't sweat it if you don't have the wording perfect and you're not really sure if "Classify" or "Group" is a better verb. Spend less time working on your scales and more time working on the assessments.

Assessments:

Tests are for self-assessment.... I give tests. But I give them mainly for students to self-assess themselves so they can figure out their strengths—so they can replicate them—and their weaknesses—so they can work on them.

....and for you.

I need to have some info to play with to figure out what to teach next.

Most of your assessment will be invisible. You'll spend a lot of time asking questions as they're doing something, listening in to convos, or just peaking over shoulders. The more you need to interrupt the process, the less valid the assessment becomes.2 Your grades will rarely be attached to a specific "thing" which is why inputting grades by time, rather than assignment, is so useful.

Use your scales to help you give feedback. Leaving feedback was and still is one of my big weaknesses. I'm ok with written stuff but I've always been awful with oral feedback. My kids either do a "Great job" or need to "Work harder." Bleh. Your scales help. Leave feedback that specifically references the skills in your scales. "Looks like you're at a 2 right now, to move forward you're going to want to practice calculating density and using the correct SI units." And yes, you're going to want to teach them to be able to do this themselves.

Grades for the Whole Game, feedback for everything else. That's what the last post was about. I'm just reminding you. But think about it when you feel you need to grade every single thing. If it's not the whole game (which it usually isn't) feedback only.

Good luck new members of the SBG Borg.

1: More on mentioning from Grant Wiggins. This came via Twitter but I've lost the source.

2: I made that up as I was typing. I have no evidence for that statement.

3: If you're on twitter, follow the #sbarbook tag and jump in. On Monday Aug 9, they're starting How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students. Most helpful book I've read in a long time.

Here are some quick tips that really helped me in the setup phase.

Topics and scales:

Cut breadth, not depth. At some point you'll find you have a ton of standards to teach. You will then realize that you can't teach that many standards. It is really tempting to try to lower your expectations so you can cover all your standards. Don't. Cut the content. Never cut depth.

Take a whole bunch of those standards and put them into the "I'm just gonna mention these" pile. When I say mention, I don't actually mean, just-say-it-and-move-on. You can spend the whole day (or more than that if you want) in your preferred method of instruction.

Usually, that means I tell my kids that they're going to need these for the state tests, but it's not going to be important for my class. I'll spend a day here or there loading some vocab, boring them with a Powerpoint, or doing an isolated lab and then just move on.1 You could certainly skip it entirely, but I'd like to give them a sporting chance at guessing on a 4-option multiple choice test.

Anchor your scale with the hardest assessments/expectations on your students. It's not uncommon for your students to need to take a common department final, a state-mandated end of course test, and an AP or AP-like test. Choose the hardest one, analyze the depth, and use that as your anchor. I didn't buy into this one until very recently, but I believe it now. It's a real problem if I'm setting my criteria based on my district benchmark, which is asking kids to read a passage and summarize what happened. Meanwhile their state test is asking them to make inferences.

Ask to see other teacher's tests in other districts. One of the things that keeps me up at night is the depth issue. I really worry that I am setting my level of expectation at a 5, while schools in Cupertino, Palo Alto, and Los Altos (insert your local high SES cities here) are asking their students to perform at a 10. I emailed about 20 teachers in other districts for copies of finals, benchmarks, whatever. Six emailed back. Since then I've seen three or four more. Mainly I learned that most teachers just use the exams provided by textbooks, but it did help me adjust a few topics and I also saw some really cool problems.

Start with the 3: I'm putting this here because MizT mentioned she didn't really get this until she read this book. I know your scoring system might be different, but you've got to start with the goal. Whatever it is you want your kids to learn, start there. Then work backwards to build the learning progression, which turns into your scale. Take a full or a half step forward to extend your scale. If it looks like backwards planning, or UbD, it's because it is. If you're going to teach that way, you should assess that way too right?

Your scales and rubrics are actually kind of useless by themselves. Sorry. I know you worked really hard on them. Your standards are meaningless until you define them with assessments and exemplars. There's a good example of that here, but it's gated. No matter how detailed and well thought out your scales are, you and your kids aren't going to really get them until they see some exemplars or they know how they'll be assessed. So don't sweat it if you don't have the wording perfect and you're not really sure if "Classify" or "Group" is a better verb. Spend less time working on your scales and more time working on the assessments.

Assessments:

Tests are for self-assessment.... I give tests. But I give them mainly for students to self-assess themselves so they can figure out their strengths—so they can replicate them—and their weaknesses—so they can work on them.

....and for you.

I need to have some info to play with to figure out what to teach next.

Most of your assessment will be invisible. You'll spend a lot of time asking questions as they're doing something, listening in to convos, or just peaking over shoulders. The more you need to interrupt the process, the less valid the assessment becomes.2 Your grades will rarely be attached to a specific "thing" which is why inputting grades by time, rather than assignment, is so useful.

Use your scales to help you give feedback. Leaving feedback was and still is one of my big weaknesses. I'm ok with written stuff but I've always been awful with oral feedback. My kids either do a "Great job" or need to "Work harder." Bleh. Your scales help. Leave feedback that specifically references the skills in your scales. "Looks like you're at a 2 right now, to move forward you're going to want to practice calculating density and using the correct SI units." And yes, you're going to want to teach them to be able to do this themselves.

Grades for the Whole Game, feedback for everything else. That's what the last post was about. I'm just reminding you. But think about it when you feel you need to grade every single thing. If it's not the whole game (which it usually isn't) feedback only.

Good luck new members of the SBG Borg.

1: More on mentioning from Grant Wiggins. This came via Twitter but I've lost the source.

2: I made that up as I was typing. I have no evidence for that statement.

3: If you're on twitter, follow the #sbarbook tag and jump in. On Monday Aug 9, they're starting How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students. Most helpful book I've read in a long time.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

SBG Implementation: Setting up the Gradebook

If you've been following along, you've already created your topic scales, designed assessments, and tracked progress.

Next we're going to actually input scores into our gradebook.

Most of our gradebooks were designed for traditional assessments only. You give points for assignments and they're averaged for the final grade. Mine does that too. There are a few programs out there that are supposed to be compatible with standards-based grading, like Global Scholar. I have zero experience with those, other than sitting through a few sales pitches, so I can't vouch for how those work in practice. You can also follow along with Shawn or Riley or the Science Goddess and see how they're doing creating their own.

I haven't hit on the one-tracker-to-rule-them-all. As such, I've got a bunch of different systems that kind of do what I want but none of them are quite perfect. I use/have used three methods for recording scores before they ultimately get recorded into my online gradebook.

I use the sticky notes to jot down quick reminders of conversations I've had with the kids. In standards-based grading the assessment type is usually irrelevant.You'll find the conversations with your kids are incredibly valuable and you'll want to write stuff down. In my best times, I can keep little notes while they're doing labs or working out problems. Often I just scribble down a few notes after the bell rings. They say things like, "Still confusing speed and velocity." or "Gets light years" or "Double check can calculate density." One of the most valuable things I've found to keep track of is who's helping whom. The kid who's always explaining things to the rest of his group knows what's going on.

The Science Goddess's excel workbook is just like mine if mine went through a few cycles of the Barry Bonds workout enhancement system. I only include overall topic scores and use conditional formatting (Green for 3/4, Yellow for 2, Red for less than 2) to keep track. I also include a column named named Proficient in All Standards and an IF-THEN formula runs through and marks yes/no if they have at least a 3 in every topic.

There are bar graphs showing the number of students scoring at each level by topic.

Lest you think I'm a master teacher, this is my second highest performing class. I have a class that's the mirror image of this one.

Setting up the Gradebook

Here's a snapshot of my gradebook. Here's Matt's.

We use PowerSchool. It looks like it's also called PowerTeacher Gradebook.

When you set up your gradebook, you should be thinking - When a student or parent reads this, can they tell what they've learned and needs to be learned? They should be thinking about what they need to learn next.

If your gradebook says Wksht Ch1.2 or Midterm, that's not so helpful.

In my gradebook I have tried to decouple the assignment from the learning wherever possible.

Instead of using categories like Quizzes, Labs, Classwork, I named each category after a topic.

I enter in scores by time, rather than by assignment. This is new this year. I moved to entering in a score every Friday instead of a score for some sort of specific assessment.1 Using the old method, when a student or parent looked online and saw a low score, they immediately wanted to make up/redo that specific assignment, whether it was a test or lab or classwork. They were focusing on the assignment rather than the learning goal. By removing the assignment entirely, I forced them to focus on the learning goal.

Additionally, differentiation is hard enough as it is. Don't make it even harder by trying to figure out how to enter grades 30 students who are working on 30 different things.2

I've changed the naming conventions over the year because of how PowerSchool formats it when I look at the gradebook. At the end of my first week teaching a new topic I'll put in something like Graphing Progress Check 1. The next week I'll put in Graphing Progress Check 2. I may simultaneously be entering a score for Motion Progress Check 4. This score is purely for reporting purposes and is zero weighted. On a good day, I can leave a comment on the score stating which particular standards they have mastered or need to work on. If you're one of those people building a gradebook, allow me to import a list of standards, attach them to a student, and check them off.

I keep track of their current level in a particular topic using Motion Topic Score or Graphing Topic Score. I overwrite this one when I see fit. I don't have an algorithm for when this gets overwritten. I err on the conservative side and I need to be pretty sure before I will overwrite a score. This may take multiple assessments but doesn't always take multiple weeks. A student might have weekly progress that looks like 1,1,2,2 but then the Topic Score is 3 because they blew me away this week. In case you're wondering, yes, I do lower my scores.

When viewed online, parents or students can click on the Final Topic Score and see a quickie version of the 4-point scale.

I like this combination of progress checks and topic scores because it keeps the record of learning intact while allowing me to not be confined by either averaging the scores or using the most current score; both of which I think have serious drawbacks.

I really wish I could display the scores by topic, instead of chronologically. Our "update" over the summer to the java version only lets us view the scores chronologically. We used to be able to sort them by category which was much better and made more sense for this method. If you have the java version of PowerSchool and know how to do this, let me know. If I can't figure out how to list them by category, I think I'm just going to fudge the due dates next year.

Final note: I can't possibly emphasize enough how much of a critical change it was for me to remove assignments entirely from my gradebook. You will encounter two situations fairly frequently once you fully embrace a standards-based system. One, your students will pick what they need to work on and will be doing something completely different from the person next to them. I anxiously await the day I can tweet that I had 30 students working on 30 different things. As of now, 6 or 7 different things is reasonably common and 3 or 4 different things is the norm. Two, you'll have one student who needs 10 different assessments for a single standard and another who showed clear mastery on the pre-test. Your online gradebook is not designed to accommodate either of those situations. Do not waste your time trying to figure out how to enter all those different grades in and then trying to explain to parents why Matthew has an A but 40% of his assignments are blank scores.

As always, leave any improvements or clarifications in the comments. I'm wrapping up this series soon. Thank you for the good comments and support. If there are any specific issues you'd like addressed - twitter, email, comment.

1: I just realized that the snapshot I used isn't spaced out weekly. The rest of the scores are pretty evenly spaced. I have no idea what I was doing with graphing.

2: It is unfortunate that grading program creators think that all students in a class will always be doing the exact same assignment on the exact same day worth the exact same amount. It is more unfortunate that this is usually true.

Next we're going to actually input scores into our gradebook.

Most of our gradebooks were designed for traditional assessments only. You give points for assignments and they're averaged for the final grade. Mine does that too. There are a few programs out there that are supposed to be compatible with standards-based grading, like Global Scholar. I have zero experience with those, other than sitting through a few sales pitches, so I can't vouch for how those work in practice. You can also follow along with Shawn or Riley or the Science Goddess and see how they're doing creating their own.

I haven't hit on the one-tracker-to-rule-them-all. As such, I've got a bunch of different systems that kind of do what I want but none of them are quite perfect. I use/have used three methods for recording scores before they ultimately get recorded into my online gradebook.

- Paper gradebook

- Sticky notes

- Excel

I use the sticky notes to jot down quick reminders of conversations I've had with the kids. In standards-based grading the assessment type is usually irrelevant.You'll find the conversations with your kids are incredibly valuable and you'll want to write stuff down. In my best times, I can keep little notes while they're doing labs or working out problems. Often I just scribble down a few notes after the bell rings. They say things like, "Still confusing speed and velocity." or "Gets light years" or "Double check can calculate density." One of the most valuable things I've found to keep track of is who's helping whom. The kid who's always explaining things to the rest of his group knows what's going on.

The Science Goddess's excel workbook is just like mine if mine went through a few cycles of the Barry Bonds workout enhancement system. I only include overall topic scores and use conditional formatting (Green for 3/4, Yellow for 2, Red for less than 2) to keep track. I also include a column named named Proficient in All Standards and an IF-THEN formula runs through and marks yes/no if they have at least a 3 in every topic.

There are bar graphs showing the number of students scoring at each level by topic.

Lest you think I'm a master teacher, this is my second highest performing class. I have a class that's the mirror image of this one.

Setting up the Gradebook

Here's a snapshot of my gradebook. Here's Matt's.

We use PowerSchool. It looks like it's also called PowerTeacher Gradebook.

When you set up your gradebook, you should be thinking - When a student or parent reads this, can they tell what they've learned and needs to be learned? They should be thinking about what they need to learn next.

If your gradebook says Wksht Ch1.2 or Midterm, that's not so helpful.

In my gradebook I have tried to decouple the assignment from the learning wherever possible.

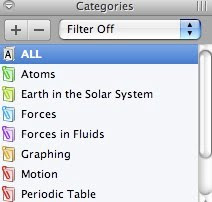

Instead of using categories like Quizzes, Labs, Classwork, I named each category after a topic.

I enter in scores by time, rather than by assignment. This is new this year. I moved to entering in a score every Friday instead of a score for some sort of specific assessment.1 Using the old method, when a student or parent looked online and saw a low score, they immediately wanted to make up/redo that specific assignment, whether it was a test or lab or classwork. They were focusing on the assignment rather than the learning goal. By removing the assignment entirely, I forced them to focus on the learning goal.

Additionally, differentiation is hard enough as it is. Don't make it even harder by trying to figure out how to enter grades 30 students who are working on 30 different things.2

I've changed the naming conventions over the year because of how PowerSchool formats it when I look at the gradebook. At the end of my first week teaching a new topic I'll put in something like Graphing Progress Check 1. The next week I'll put in Graphing Progress Check 2. I may simultaneously be entering a score for Motion Progress Check 4. This score is purely for reporting purposes and is zero weighted. On a good day, I can leave a comment on the score stating which particular standards they have mastered or need to work on. If you're one of those people building a gradebook, allow me to import a list of standards, attach them to a student, and check them off.

I keep track of their current level in a particular topic using Motion Topic Score or Graphing Topic Score. I overwrite this one when I see fit. I don't have an algorithm for when this gets overwritten. I err on the conservative side and I need to be pretty sure before I will overwrite a score. This may take multiple assessments but doesn't always take multiple weeks. A student might have weekly progress that looks like 1,1,2,2 but then the Topic Score is 3 because they blew me away this week. In case you're wondering, yes, I do lower my scores.

When viewed online, parents or students can click on the Final Topic Score and see a quickie version of the 4-point scale.

I like this combination of progress checks and topic scores because it keeps the record of learning intact while allowing me to not be confined by either averaging the scores or using the most current score; both of which I think have serious drawbacks.

I really wish I could display the scores by topic, instead of chronologically. Our "update" over the summer to the java version only lets us view the scores chronologically. We used to be able to sort them by category which was much better and made more sense for this method. If you have the java version of PowerSchool and know how to do this, let me know. If I can't figure out how to list them by category, I think I'm just going to fudge the due dates next year.

Final note: I can't possibly emphasize enough how much of a critical change it was for me to remove assignments entirely from my gradebook. You will encounter two situations fairly frequently once you fully embrace a standards-based system. One, your students will pick what they need to work on and will be doing something completely different from the person next to them. I anxiously await the day I can tweet that I had 30 students working on 30 different things. As of now, 6 or 7 different things is reasonably common and 3 or 4 different things is the norm. Two, you'll have one student who needs 10 different assessments for a single standard and another who showed clear mastery on the pre-test. Your online gradebook is not designed to accommodate either of those situations. Do not waste your time trying to figure out how to enter all those different grades in and then trying to explain to parents why Matthew has an A but 40% of his assignments are blank scores.

As always, leave any improvements or clarifications in the comments. I'm wrapping up this series soon. Thank you for the good comments and support. If there are any specific issues you'd like addressed - twitter, email, comment.

1: I just realized that the snapshot I used isn't spaced out weekly. The rest of the scores are pretty evenly spaced. I have no idea what I was doing with graphing.

2: It is unfortunate that grading program creators think that all students in a class will always be doing the exact same assignment on the exact same day worth the exact same amount. It is more unfortunate that this is usually true.

Sunday, June 6, 2010

SBG Implementation: Tracking Progress

So far we've designed our topic scales and written out a test. Now we're going to track our progress. By the end of this post you should have a pretty good idea of what my typical assessment cycle looks like. Matt Townsley has more thoughts here.

Step three in my adventures into standards-based grading: Tracking progress

I ask students to numerically track their individual progress for each topic scale.The purpose of the tracking sheet is to help them track their progress and self-assess. The tracking sheet is designed for student use.

For every topic I give students something like this:

Tracking Atoms

They store these in a two-pocket portfolio.1

Specific features:

1. Topic name at the top. My original tracking sheet didn't have a separate topic name, only a learning goal. I don't know what I was thinking.

2. A graph to track progress. The y-axis is a 0-4 score. The x-axis is individual assessments.

3. On the bottom you'll see the 0-4 scale along with a condensed form of my specific learning goals. I print out and posterize a slightly more detailed version on my bulletin board.

4. On the back there's a checklist of each specific standard. The far left column has the letter that matches up to questions on the tests. The next column is chapter and section the information can be found in the book.

How to use it:

Again, this tracking sheet is for them. They should get two things from it. Am I making progress? What do I need to work on next?

Testing day in a nutshell:

Step 3: Score the test. I'm a big believer in immediate feedback. I need to know how I'm doing right away. Ideally, I can get feedback as I go. If you're a Montessori kind of person, they have all these self-correcting activities. If you're a coach of a sport, you teach music, or art, you guide them as they go. You probably have some self-checking worksheets. If I can't get my feedback as I go, then I want it as soon as I'm done. We go over the answers immediately. I want their test in front of them so they can immediately compare. If I want to input the score into the gradebook1 I have them copy their answers down onto a half sheet of paper and turn that in.

Here's how the scoring system works. They get a 2.0 if they got 100% correct all the way up to where it says 3.0. If scribd and the pdf export didn't mess up the formatting, that means all the questions on the first page. If they missed anything, even one thing, that's less than a 2.0. If they got ALL the 2.0 questions and ALL the 3.0 questions right, that's a 3.0. 4.0 means everything is 100% correct. I use half points as well as full so 1.5 and 2.5 are fair game. Why insist on 100%? Because your grades should have meaning. A student scoring a 2.0 in my class will understand, at minimum, all of the simple concepts on that topic. It dilutes the meaning of the score if it means, "Carina gets most of the simple concepts but there's something she's fuzzy on. That's different from the thing that Michael is unclear on, but his score is also the same." It's called standards-based grading for a reason. Their grade is based on meeting a well-defined standard.

Step 4: Track progress. I have my students write in the date in the line to the right of the graph and then do a simple bar graph. They lightly shade in the bar. You will be amazed at how often students point out the progress they've made. It is also incredibly powerful to point to the tracking sheet of the person next to them. My students usually think students are just born smart. It's a big deal for them to see that the straight A student sitting next to them also scored a 0.5 on the first assessment.

On the back, they traffic light each standard. They match the letter next to each test question with the corresponding standard. I just have them mark a plus/check/or minus for each one. I tell them that a plus means they'll understand it the rest of their lives, a check means they've pretty much got it but need a bit more practice, a minus means anywhere from "I get some parts of it" to "What class is this again?" This checklist is my way of getting the direct remediation goodness that skill-lists offer while maintaining the learning progression that topic scales build in.

The front graph is almost always based on test results. They might traffic light a single standard after doing an assignment, notes, lecture, or whatever. Anytime they feel like they've got it now, they can go ahead and put a plus next to a standard.

Step 5: Set a goal. Immediately after filling in their tracking sheet I have them set a goal. This year I just had them write at the bottom of their test,"The standard I will work on next is _______. I am going to____." I've tried a few different sentences frames but haven't really found a difference in how they perform. I think next year I might just include a separate goal sheet in their portfolios. I'd like to create a single reference place with the ultimate goal of being able to help them determine which specific strategies helped them achieve their learning goals.

Step 6: Start remediation. This one is always tricky. I usually go over the answers with a Keynote preso so the last slide will often include specific options I have prepped. They also have a textbook, an interactive reader, and a workbook. Most often it looks something like this where I have them break off into groups focusing on selected topics. I haven't gotten to the point where I can have 30 students working on 30 different things at 30 different levels. If you've got the technology and access, I know some teachers who screencast everything and send their kids off to different stations to watch those. Right now, I'm just happy that I've moved beyond all 30 students doing the exact same thing. I get them going then direct teach for a few minutes at each table. A quick description is here.

I have 53 minute periods so a typical test might take 15 minutes. It takes another 15 minutes to score, track, set a goal and get somewhere. That leaves a good 20 minutes of individualized time.3 If you're pressed for time or you want longer and more in depth tests, have them set a goal for the next day and just walk in and get going.

Sticking Points:

Your students have no idea how to help themselves. It's really hard to get this going and takes a ton of front-loading if they're not used to taking responsibility for their own learning. It took a lot of modeling. I think the first test I gave we spent a whole period just scoring it and doing the bar graph and traffic lighting. The next day we spent half the period writing goals. There are a special few that still just can't figure it out by the end of the year and wait for me to come around. I don't know what to do with those kids. Having them create a specific plan helped a lot. One of my major mistakes was just thinking I could tell them what they needed to learn and they'd go off and learn it. Totally not happening. Setting written goals was a big step and offering a range of choices was another. I was hoping to wean them off choosing something I had created and get them to create their own plan but I didn't have a lot of success with that.

It seems like an insane amount of prep for different kids to be working on different things. It is at first. No question. But you can reuse most of the same stuff for the duration of a topic. The student will get what they're supposed to get, move up the ladder, and work on something different next time. So, yes, there's a fair amount of prep the first time, but after that it takes care of itself. I'm not a master organizer, but you could have a bunch of numbered folders or trays on a back table. When you put up the choice list (or leave it up throughout the unit), they'd just match the standard to the number of the file folder. The internet is your friend so if you have access, make use of all the applets and videos you can find. The few kids at my school that have working internet access at home will tell me that a few minutes on an applet I pointed them to is worth a whole week of me blabbering at them in class. If I had computers in my class it would probably be pretty easy to send them to specific websites to get help.

In the last post, I added a fourth and fifth principle to Dan Meyer's. I've tried to set up my tests and tracking sheets in such a way that it does most of the work for me. I'm hoping to be as invisible as possible in this whole process. The more I interject myself into it, the more likely it is a student is going to attribute success (and failure) to me instead of to him/herself.

As always, leave any improvements/suggestions/modifications in the comments. I tend to write these posts at 11:30 at night so if something isn't coherent, I'll explain more as needed.

Edit: Probably should include this link again: http://www.box.net/shared/6xplu3btfy It's the Word 2004 (mac) template for the tracking sheets.

1: I buy these for them in the beginning of the year along with a spiral notebook. I get the notebooks from Target. Office Depot usually has the portfolios in store for, I think, 29 cents each during back to school sales.

2: Don't worry, the gradebook post is coming next.

3: Ok, by the end of the year it takes that long. The first few tests take an entire period and remediation follows the next day. We get pretty quick as the year progresses though.

Step three in my adventures into standards-based grading: Tracking progress

I ask students to numerically track their individual progress for each topic scale.The purpose of the tracking sheet is to help them track their progress and self-assess. The tracking sheet is designed for student use.

For every topic I give students something like this:

Tracking Atoms

They store these in a two-pocket portfolio.1

Specific features:

1. Topic name at the top. My original tracking sheet didn't have a separate topic name, only a learning goal. I don't know what I was thinking.

2. A graph to track progress. The y-axis is a 0-4 score. The x-axis is individual assessments.

3. On the bottom you'll see the 0-4 scale along with a condensed form of my specific learning goals. I print out and posterize a slightly more detailed version on my bulletin board.

4. On the back there's a checklist of each specific standard. The far left column has the letter that matches up to questions on the tests. The next column is chapter and section the information can be found in the book.

How to use it:

Again, this tracking sheet is for them. They should get two things from it. Am I making progress? What do I need to work on next?

Testing day in a nutshell:

- Hand out test.

- Kids take test.

- We score the test immediately.

- Track progress.

- Set next individual goal.

- Start immediate remediation.

Step 3: Score the test. I'm a big believer in immediate feedback. I need to know how I'm doing right away. Ideally, I can get feedback as I go. If you're a Montessori kind of person, they have all these self-correcting activities. If you're a coach of a sport, you teach music, or art, you guide them as they go. You probably have some self-checking worksheets. If I can't get my feedback as I go, then I want it as soon as I'm done. We go over the answers immediately. I want their test in front of them so they can immediately compare. If I want to input the score into the gradebook1 I have them copy their answers down onto a half sheet of paper and turn that in.

Here's how the scoring system works. They get a 2.0 if they got 100% correct all the way up to where it says 3.0. If scribd and the pdf export didn't mess up the formatting, that means all the questions on the first page. If they missed anything, even one thing, that's less than a 2.0. If they got ALL the 2.0 questions and ALL the 3.0 questions right, that's a 3.0. 4.0 means everything is 100% correct. I use half points as well as full so 1.5 and 2.5 are fair game. Why insist on 100%? Because your grades should have meaning. A student scoring a 2.0 in my class will understand, at minimum, all of the simple concepts on that topic. It dilutes the meaning of the score if it means, "Carina gets most of the simple concepts but there's something she's fuzzy on. That's different from the thing that Michael is unclear on, but his score is also the same." It's called standards-based grading for a reason. Their grade is based on meeting a well-defined standard.

Step 4: Track progress. I have my students write in the date in the line to the right of the graph and then do a simple bar graph. They lightly shade in the bar. You will be amazed at how often students point out the progress they've made. It is also incredibly powerful to point to the tracking sheet of the person next to them. My students usually think students are just born smart. It's a big deal for them to see that the straight A student sitting next to them also scored a 0.5 on the first assessment.

On the back, they traffic light each standard. They match the letter next to each test question with the corresponding standard. I just have them mark a plus/check/or minus for each one. I tell them that a plus means they'll understand it the rest of their lives, a check means they've pretty much got it but need a bit more practice, a minus means anywhere from "I get some parts of it" to "What class is this again?" This checklist is my way of getting the direct remediation goodness that skill-lists offer while maintaining the learning progression that topic scales build in.

The front graph is almost always based on test results. They might traffic light a single standard after doing an assignment, notes, lecture, or whatever. Anytime they feel like they've got it now, they can go ahead and put a plus next to a standard.

Step 5: Set a goal. Immediately after filling in their tracking sheet I have them set a goal. This year I just had them write at the bottom of their test,"The standard I will work on next is _______. I am going to____." I've tried a few different sentences frames but haven't really found a difference in how they perform. I think next year I might just include a separate goal sheet in their portfolios. I'd like to create a single reference place with the ultimate goal of being able to help them determine which specific strategies helped them achieve their learning goals.

Step 6: Start remediation. This one is always tricky. I usually go over the answers with a Keynote preso so the last slide will often include specific options I have prepped. They also have a textbook, an interactive reader, and a workbook. Most often it looks something like this where I have them break off into groups focusing on selected topics. I haven't gotten to the point where I can have 30 students working on 30 different things at 30 different levels. If you've got the technology and access, I know some teachers who screencast everything and send their kids off to different stations to watch those. Right now, I'm just happy that I've moved beyond all 30 students doing the exact same thing. I get them going then direct teach for a few minutes at each table. A quick description is here.

I have 53 minute periods so a typical test might take 15 minutes. It takes another 15 minutes to score, track, set a goal and get somewhere. That leaves a good 20 minutes of individualized time.3 If you're pressed for time or you want longer and more in depth tests, have them set a goal for the next day and just walk in and get going.

Sticking Points:

Your students have no idea how to help themselves. It's really hard to get this going and takes a ton of front-loading if they're not used to taking responsibility for their own learning. It took a lot of modeling. I think the first test I gave we spent a whole period just scoring it and doing the bar graph and traffic lighting. The next day we spent half the period writing goals. There are a special few that still just can't figure it out by the end of the year and wait for me to come around. I don't know what to do with those kids. Having them create a specific plan helped a lot. One of my major mistakes was just thinking I could tell them what they needed to learn and they'd go off and learn it. Totally not happening. Setting written goals was a big step and offering a range of choices was another. I was hoping to wean them off choosing something I had created and get them to create their own plan but I didn't have a lot of success with that.

It seems like an insane amount of prep for different kids to be working on different things. It is at first. No question. But you can reuse most of the same stuff for the duration of a topic. The student will get what they're supposed to get, move up the ladder, and work on something different next time. So, yes, there's a fair amount of prep the first time, but after that it takes care of itself. I'm not a master organizer, but you could have a bunch of numbered folders or trays on a back table. When you put up the choice list (or leave it up throughout the unit), they'd just match the standard to the number of the file folder. The internet is your friend so if you have access, make use of all the applets and videos you can find. The few kids at my school that have working internet access at home will tell me that a few minutes on an applet I pointed them to is worth a whole week of me blabbering at them in class. If I had computers in my class it would probably be pretty easy to send them to specific websites to get help.

In the last post, I added a fourth and fifth principle to Dan Meyer's. I've tried to set up my tests and tracking sheets in such a way that it does most of the work for me. I'm hoping to be as invisible as possible in this whole process. The more I interject myself into it, the more likely it is a student is going to attribute success (and failure) to me instead of to him/herself.

As always, leave any improvements/suggestions/modifications in the comments. I tend to write these posts at 11:30 at night so if something isn't coherent, I'll explain more as needed.

Edit: Probably should include this link again: http://www.box.net/shared/6xplu3btfy It's the Word 2004 (mac) template for the tracking sheets.

1: I buy these for them in the beginning of the year along with a spiral notebook. I get the notebooks from Target. Office Depot usually has the portfolios in store for, I think, 29 cents each during back to school sales.

2: Don't worry, the gradebook post is coming next.

3: Ok, by the end of the year it takes that long. The first few tests take an entire period and remediation follows the next day. We get pretty quick as the year progresses though.

SBG Implementation: Creating Assessments

Programming note: I'm breaking this post in to two parts. This one is on the test itself and the next will be on scoring and tracking progress.

Citation: I forgot to mention that I started off with the base system outlined in Classroom Assessment and Grading that Work and have spun it off a bit to better fit my context and style.

This is the second in a series on the process I went though implementing standards-based grading in my class. Part one here. If you haven't read that one yet, you should go back. You'll need to understand the 0-4 system before you read the rest.

Just as a refresher, here are the ground rules:

And fifth: The ultimate goal is self-assessment. Any assessment policy should help students to become better self-assessors.

Jargon alert: I use the term "standards" to refer to your in class learning goals, not your state standards. I use the term test and quiz interchangeably. I'm specifically referring to a written assessment that a student takes by him/herself

Step two in my adventures into standards-based grading: Creating Assessments

Before you get overly excited, this is not the post where you're going to learn how to write really rich and interesting problems. Look to your right. Most of those blogs devote themselves to that exact purpose. Grace has a good, short post on testing conceptual development. Personally, I like to use the rich problems for teaching, but not so much for written assessment. Context is everything here and I'd love for you to comment that I'm wrong about this. I have so many English learners that I find that I'm not really testing what I think I'm testing (h/t @optimizingke). My written test questions tend to be straight vanilla.

What I am going to write about today is test formatting. Not very glamorous, but it's one of those things that will make your transition much easier.

Tests exist so you and your students can tell where they are and what needs to be done next. The test itself should provide feedback.

There are many other ways to do this but tests have a couple of advantages. One: They're darn efficient. You can knock out a test in 15 minutes and get kids working on remediation in the same period. Two: There's a paper trail. It helps students to see how their thinking has progressed and to analyze the mistakes that they've made again and again (and again).

I definitely use multiple methods of assessment, and in fact it's necessary in any quality assessment system. However, written tests are the bread and butter for most teachers so that's what we're going to focus on here.

Here's a sample test. Most of my problems are drawn from sample state test questions, textbooks, and what we develop as a department:2

atomslg2

Specific features:

1. In the top right you'll see the topic name and which assessment number it is. They're going to reassess a lot. In my class that's usually a minimum 4-6 times for a single topic in class and even more if they want to come after school. You've got to have a way to keep them/you organized.

2. I wrote the learning goal on top. I'm actually planning to remove that. I think my original tracking sheets only had the learning goal on top and not the topic name. It was my way to help the kids match up the tracking sheet to the assessment. Now that I put the topic name on both, it's superfluous. You would think having the learning goal on the top would be like a cheat sheet to help my students answer the questions. Sadly, you'd be wrong. If anyone has a good reason for me to leave it, let me know.

3. After each test question, there's a letter that matches the question to the standard listed in their tracking sheet. Mostly, the reason for this is to help you and your students track their progress on each standard. There's a second plus. It serves as a self-check when you're writing your test questions. If you can't match up a question directly to a standard, or multiple standards, you need to edit your question, your standards, or both.

4. Questions are separated into 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 questions. The front page consists of simple ideas, usually vocabulary or basic knowledge. The 3.0 questions are the more complex ideas. The 4.0 question has not been addressed in class but if they understand the complex ideas, they can apply those to arrive at a solution.

Most teachers I've observed cluster by problem type (multiple choice together, then matching, then short answer at the end.)

If you're clustering by problem type, please stop. It's unhelpful. You and your students should be able to identify some sort of pattern by looking at the results of the tests. That's really hard to do on tests like this. Unless your goal is to help students figure out what type of question they have the most difficulty with, I can't think of a good reason for doing this.

The second most common method is to cluster by standard. I like this method, but don't use it. I really like it for some purposes and designed our department benchmarks in this way. The strength is that there's a direct line between "what I missed on this test" and "what I need to work on." Remediation is really straightforward. Since I cluster my test questions by complexity, there's an extra step they need to work through to figure out what needs to be done next. It's not a difficult step, but some students will need more hand holding than I prefer.

So why do I choose to group my tests in this method? The most obvious is that this is how my grading scale works. It's really clear both to my students and to myself what score the test will receive. There's a better reason for choosing this method though.

I often come back to how I think using topics helps create connections across standards better than skill-based assessments and here's another example. In a skill-based assessment, students can easily see what specific standard they need help on, however because of the very format of the assessment (chunked by standards and often on separate pieces of paper) it is harder to look for patterns of errors and broad misconceptions. In a topic-based system, it is easier to see systematic errors.3

Imagine a student missing questions 7 and 9 on the test above. I could ask them to go and learn more about both states of matter and the kinetic molecular theory. In a skills-based assessment that would be my default, especially if those standards were assessed at separate times. In a topic-based system, when I read the answers together I might realize that the student has a knowledge gap that's affecting both questions. For example he/she might not understand the relationship between temperature and molecular motion, which is necessary to answer both questions.

Additionally, by clustering from simple to complex, I can quickly focus on a few common problem areas. If they're stuck on the first page, it's usually something like, "He has no idea what an atom is so he's just guessing at everything" or "She is confusing velocity and speed." If the difficulties occur on the 3.0 questions, I can rule out all of the simple stuff because I've seen that they've mastered that already.

This is totally possible to do with an assessment grouped by standard. I think the trade off of more direct remediation for making connections/ease of scoring is worth it.

All of this is a really long-winded way of saying that if you're going to implement a topic-based system, it makes sense to design your assessments by topic. Since you've taken the time to build a learning progression into your topic, keep that intact as well.

Sticking Points:

You can't figure out how to cram an entire topic into a single test without making it the SAT. You're aiming for frequent smaller assessments rather than a big one at the end of a unit. Don't feel the need to cram every last question in. Get to it next time. Notice that the second question only deals with the charge of a neutron. In other assessments I would have the properties of protons or electrons as well. Generally, if a student doesn't know the neutron is neutral, they're also not going to know the proton is positive and electron is negative. I don't feel the need to put all three on the same test. I just want to get an idea for what they know so I know what to teach next.

You've made this great topic scale but don't know how to write questions for it. I've found that commonly the problem isn't that I can't come up with a question for a standard, it's that the standard doesn't lend itself to being answered in a standard testing format. You just can't assess your state's oral language standards in writing. In your classroom, anything is an assessment. You've got your topic scales, get them to do whatever it is they need to do and evaluate it against those scales. My textbook's assessment software includes questions with pictures of a triple-beam balance and different arrows pointing at the numbers. You're supposed to then tell the mass of the object on the balance. I could do that. Or I could not be the laziest person ever and get out the triple beam balances and walk around as they determine the mass of different objects. For the most part, teachers seem to be pretty good about understanding that different modes of assessment are necessary. We're not as good at realizing that those other modes should be replacing written tests. Most teachers I know would start with having the actual triple beam balances out but then pull out the written tests later. Either they don't think it should count unless it's on a test or they're worried about CYA or they're just in the habit of putting everything on a test. Break the habit. Everything doesn't need to eventually show up in multiple choice format.

Next up: Scoring the assessment and tracking progress

1: Forgot to mention this last time. The book Mount Pleasant is about the high school my kids feed into. Don't buy it, but if you're in California you might want to check it out from your library and read what our current insurance commissioner and aspiring governor thinks of public schools.

2: Teaser: After the implementation series is done, I'm going to start on the joys of common assessments. Most teachers I talk to hate them. If you do, you're doing it wrong. More likely, your school is doing it to you wrong.

3: It's easier for me at least. I don't have a good system, or even a mediocre system, for teaching students to look for patterns of errors and misconceptions.

Citation: I forgot to mention that I started off with the base system outlined in Classroom Assessment and Grading that Work and have spun it off a bit to better fit my context and style.

This is the second in a series on the process I went though implementing standards-based grading in my class. Part one here. If you haven't read that one yet, you should go back. You'll need to understand the 0-4 system before you read the rest.

Just as a refresher, here are the ground rules:

- There is no canon for SBG.

- Context is everything.1

- It doesn't matter when you learn it as long as you learn it.

- My assessment policy needs to direct my remediation of your skills.

- My assessment policy needs incentivize your own remediation.

And fifth: The ultimate goal is self-assessment. Any assessment policy should help students to become better self-assessors.

Jargon alert: I use the term "standards" to refer to your in class learning goals, not your state standards. I use the term test and quiz interchangeably. I'm specifically referring to a written assessment that a student takes by him/herself

Step two in my adventures into standards-based grading: Creating Assessments

Before you get overly excited, this is not the post where you're going to learn how to write really rich and interesting problems. Look to your right. Most of those blogs devote themselves to that exact purpose. Grace has a good, short post on testing conceptual development. Personally, I like to use the rich problems for teaching, but not so much for written assessment. Context is everything here and I'd love for you to comment that I'm wrong about this. I have so many English learners that I find that I'm not really testing what I think I'm testing (h/t @optimizingke). My written test questions tend to be straight vanilla.

What I am going to write about today is test formatting. Not very glamorous, but it's one of those things that will make your transition much easier.

Tests exist so you and your students can tell where they are and what needs to be done next. The test itself should provide feedback.

There are many other ways to do this but tests have a couple of advantages. One: They're darn efficient. You can knock out a test in 15 minutes and get kids working on remediation in the same period. Two: There's a paper trail. It helps students to see how their thinking has progressed and to analyze the mistakes that they've made again and again (and again).

I definitely use multiple methods of assessment, and in fact it's necessary in any quality assessment system. However, written tests are the bread and butter for most teachers so that's what we're going to focus on here.

Here's a sample test. Most of my problems are drawn from sample state test questions, textbooks, and what we develop as a department:2

atomslg2

Specific features:

1. In the top right you'll see the topic name and which assessment number it is. They're going to reassess a lot. In my class that's usually a minimum 4-6 times for a single topic in class and even more if they want to come after school. You've got to have a way to keep them/you organized.

2. I wrote the learning goal on top. I'm actually planning to remove that. I think my original tracking sheets only had the learning goal on top and not the topic name. It was my way to help the kids match up the tracking sheet to the assessment. Now that I put the topic name on both, it's superfluous. You would think having the learning goal on the top would be like a cheat sheet to help my students answer the questions. Sadly, you'd be wrong. If anyone has a good reason for me to leave it, let me know.

3. After each test question, there's a letter that matches the question to the standard listed in their tracking sheet. Mostly, the reason for this is to help you and your students track their progress on each standard. There's a second plus. It serves as a self-check when you're writing your test questions. If you can't match up a question directly to a standard, or multiple standards, you need to edit your question, your standards, or both.

4. Questions are separated into 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 questions. The front page consists of simple ideas, usually vocabulary or basic knowledge. The 3.0 questions are the more complex ideas. The 4.0 question has not been addressed in class but if they understand the complex ideas, they can apply those to arrive at a solution.

Most teachers I've observed cluster by problem type (multiple choice together, then matching, then short answer at the end.)

If you're clustering by problem type, please stop. It's unhelpful. You and your students should be able to identify some sort of pattern by looking at the results of the tests. That's really hard to do on tests like this. Unless your goal is to help students figure out what type of question they have the most difficulty with, I can't think of a good reason for doing this.

The second most common method is to cluster by standard. I like this method, but don't use it. I really like it for some purposes and designed our department benchmarks in this way. The strength is that there's a direct line between "what I missed on this test" and "what I need to work on." Remediation is really straightforward. Since I cluster my test questions by complexity, there's an extra step they need to work through to figure out what needs to be done next. It's not a difficult step, but some students will need more hand holding than I prefer.

So why do I choose to group my tests in this method? The most obvious is that this is how my grading scale works. It's really clear both to my students and to myself what score the test will receive. There's a better reason for choosing this method though.

I often come back to how I think using topics helps create connections across standards better than skill-based assessments and here's another example. In a skill-based assessment, students can easily see what specific standard they need help on, however because of the very format of the assessment (chunked by standards and often on separate pieces of paper) it is harder to look for patterns of errors and broad misconceptions. In a topic-based system, it is easier to see systematic errors.3

Imagine a student missing questions 7 and 9 on the test above. I could ask them to go and learn more about both states of matter and the kinetic molecular theory. In a skills-based assessment that would be my default, especially if those standards were assessed at separate times. In a topic-based system, when I read the answers together I might realize that the student has a knowledge gap that's affecting both questions. For example he/she might not understand the relationship between temperature and molecular motion, which is necessary to answer both questions.

Additionally, by clustering from simple to complex, I can quickly focus on a few common problem areas. If they're stuck on the first page, it's usually something like, "He has no idea what an atom is so he's just guessing at everything" or "She is confusing velocity and speed." If the difficulties occur on the 3.0 questions, I can rule out all of the simple stuff because I've seen that they've mastered that already.

This is totally possible to do with an assessment grouped by standard. I think the trade off of more direct remediation for making connections/ease of scoring is worth it.

All of this is a really long-winded way of saying that if you're going to implement a topic-based system, it makes sense to design your assessments by topic. Since you've taken the time to build a learning progression into your topic, keep that intact as well.

Sticking Points:

You can't figure out how to cram an entire topic into a single test without making it the SAT. You're aiming for frequent smaller assessments rather than a big one at the end of a unit. Don't feel the need to cram every last question in. Get to it next time. Notice that the second question only deals with the charge of a neutron. In other assessments I would have the properties of protons or electrons as well. Generally, if a student doesn't know the neutron is neutral, they're also not going to know the proton is positive and electron is negative. I don't feel the need to put all three on the same test. I just want to get an idea for what they know so I know what to teach next.

You've made this great topic scale but don't know how to write questions for it. I've found that commonly the problem isn't that I can't come up with a question for a standard, it's that the standard doesn't lend itself to being answered in a standard testing format. You just can't assess your state's oral language standards in writing. In your classroom, anything is an assessment. You've got your topic scales, get them to do whatever it is they need to do and evaluate it against those scales. My textbook's assessment software includes questions with pictures of a triple-beam balance and different arrows pointing at the numbers. You're supposed to then tell the mass of the object on the balance. I could do that. Or I could not be the laziest person ever and get out the triple beam balances and walk around as they determine the mass of different objects. For the most part, teachers seem to be pretty good about understanding that different modes of assessment are necessary. We're not as good at realizing that those other modes should be replacing written tests. Most teachers I know would start with having the actual triple beam balances out but then pull out the written tests later. Either they don't think it should count unless it's on a test or they're worried about CYA or they're just in the habit of putting everything on a test. Break the habit. Everything doesn't need to eventually show up in multiple choice format.

Next up: Scoring the assessment and tracking progress

1: Forgot to mention this last time. The book Mount Pleasant is about the high school my kids feed into. Don't buy it, but if you're in California you might want to check it out from your library and read what our current insurance commissioner and aspiring governor thinks of public schools.

2: Teaser: After the implementation series is done, I'm going to start on the joys of common assessments. Most teachers I talk to hate them. If you do, you're doing it wrong. More likely, your school is doing it to you wrong.

3: It's easier for me at least. I don't have a good system, or even a mediocre system, for teaching students to look for patterns of errors and misconceptions.

Saturday, May 29, 2010

SBG Implementation: Topic Scales

For those of you not active in the twitterverse, among the people I follow there's been an increasing interest in standards-based grading. Sam Shah called us an "inspiring ideological cult." I'm taking that as a compliment.

With that in mind I'm going to explain my process for implementation.

Assumption: You already have a basic idea of what standards-based grading is. If not, go read every post by Shawn or Matt and come back.

Things to keep in mind:

What I've developed has been reasonably successful for my students, YMMV. Leave suggestions for improvement in the comments or send something through twitter or email.

Jargon alert: I'm going to use the word "standard" to refer to any unit of knowledge or skill you want to teach and assess. These are also variously referred to as learning goals or targets. A topic, also called a strand, is a collection of those standards that are grouped together in a meaningful way. Do not confuse standards-based grading with your state standards or standardization, although they probably will be related.

Step one in my adventure into standards-based grading: Building Topic Scales

Ok, maybe this isn't the first, first, first step, but it's the first meaningful one and most of us start here.

Even if you are not planning to implement standards-based grading, this is a valuable activity to do. You will become a better teacher just by going through this process.

For a quick review on why I chose to use topic scales, check out an older post.

What you're doing is setting levels of proficiency for each standard you hope to assess in your classroom. You are deciding on a target. My scoring system looks like this:

0 = No evidence of learning

1 = Can do most of the simple stuff with help

2 = Can do all of the simple stuff

3 = Can do all of the simple stuff and all of the complex stuff

4 = Can go beyond what was directly taught in class

I also have half points, like 2.5.

Group the standards into topics. This is a bit of vi vs. emacs. I'm not sure there's a right answer here.1 The math peeps generally opt for a straight skills list. I've noted my disagreement with that and am sticking to it. The downside of topics is that it is slightly more difficult for a student to tell what he/she needs to remediate. There's an extra step that some kids have trouble negotiating. On the plus side, topics facilitate connections between skills. Most of us have a good sense about what to group into a topic. In content classes like science or history, your existing units will fit pretty well. There are interesting ways to group science and history beyond Energy and Ancient Egypt but I won't get into that now. If you're ELA you can have Persuasive Writing, Genre or the have a topic for each of the Writing Traits if you use those. Math might have Order of Operations, Percent and Decimals, Fractions, Probability. Each topic should have one or two really big ideas. I think somewhere between 10 and 20 topics per year is manageable. Too few and they start to lack coherence. Too many become unmanageable.

Start with the 3. What are the complex ideas/concepts/skills that I want my students to know or be able to do? Ideally, this is a process you're sharing with your department. Probably, you're flying solo here as I was so I drew from a variety of sources. I started with my CA standards, framework, and looked at released test questions. I've recently found performance level descriptors (pdf) that I used to adjust my standards a little. I also took a look at the standards for the high school science classes and used my own experiences with college and laboratory science to some degree. Be specific about what you want your kids to learn. "Learn fractions" isn't that helpful. "Add/subtract fractions with two-digit denominators" is much better.

Your primary concern here is twofold: What do my students need to learn? and At what depth do they need to learn it? If you're looking for help on depth, Bloom's and Marzano/Kendall's taxonomies were fairly helpful, as was Webb's Depth of Knowledge (pdf).

Backwards plan the 2. At this point you should have somewhere between ten and twenty topics. In my Forces in Fluids scale, my 3.0 included determining the density of an object, using Archimedes principle, and understanding how to manipulate the buoyancy of an object. You'll need to break these standards into a learning progression. Ask yourself, What do my students need to know to be able to do this stuff? Well they needed some basic vocab: density, buoyant force, pressure. They needed some measuring skills and a couple of SI units. They needed to understand that things sunk if they were more dense than the liquid they were immersed in. That became my 2.0. You are trying to build a natural progression up your scale. Notice that the things in the 2.0 are needed to learn the more complex items. I'm not bombarding them with 50 different vocabulary words. For each topic I try to limit the vocabulary and memorization to the specific items that they'll need to understand the concept.

Set your 4. The 4.0 exists for one reason. If you directly taught it in class, it's memorization. It doesn't matter if it's a name, date, or the causes of the Civil War. Whether it's a simple idea or a complex idea, it's still our little birdies upchucking facts onto their papers. So your question for 4.0 is, Where do I want them to go with this? In my classroom, this usually takes a few different forms. Sometimes I ask them to connect different information together in news ways, such as the relationship between metals having free valence electrons and also being conductive. I teach them the facts necessary to make that connection. I also try to teach them how to connect information.2 It's up to them to close the final gap. Other times I'll look at my high school standards and set the next natural step as the 4.0. In this case, I will spend a day or so directly teaching a few things. I violate my own don't-directly-teach-it rule here. Specifically, I wanted my kids to be exposed to balancing equations. You don't really need to know how to do it in 8th grade but our high school chem teachers spend forever on it. I didn't think it would be fair to require all students to learn how to balance equations so I compromised by setting it at the 4.0. I think of it as bonus knowledge. My other most common 4.0 style of question is just adding an extra half step onto an existing 3.0 level problem. The 8th grade standards for determining speed are very basic "You go 10 miles in two hours, what's your average speed?" problems. 4.0 might include finding an average of multiple trips or determining the speed you'll need to travel to obtain a certain average (I go 10 miles in two hours, if I want to maintain an average speed of 8 mph....). The higher levels on all of those taxonomies are helpful here as well.

Quick check: You have 10-20 topics. If you were to read the topic scales starting at the 2.0 and working your way up, it follows a natural and logical learning progression. Your standards are grouped in a way that also makes sense. They're related and when students learn one standard in a topic, it helps them with the other standards at the same time.

Write out your assessments. I wrote out a pretty representative sample of all the questions I planned to put on my tests. It will be a back and forth process of writing problems based on your standards as well as revising your standards because you realize that's not quite what you wanted your students to do. I'm a huge-mungous believer that if you plan to assess it, you need to teach it. Look at your questions. If it states, "Analyze the effects of NAFTA on the economy and labor conditions in Mexico," then not only do you need to teach them about NAFTA, but you need to teach them how to analyze. Adjust your standards accordingly.

That's basically it. Look at your standards. Decide what proficient "looks like." Backwards plan how to get there. It took me a solid weekend to get a good rough draft. I used my first topic and immediately realized I had to revise things. Don't make 150 copies of all of your topic lists and laminate posters until you've got a few topics under your belt.

Science example: I have a topic called Atoms. The big idea is that all matter is made of atoms and that the existence of atoms can explain macroscopic phenomena. In the end, I want them to understand how temperature, pressure, and volume are related in a gas and the relationship between atomic motion, energy, and the state of matter. This is my 3. What do they need to know in order to get there? Well they've got to understand some basic vocabulary: matter, atom, solid, liquid, gas, pressure, temperature, volume. They've got to be able to differentiate between matter and non-matter. Since the 3.0 is centered around physical changes, they'll also need to know what properties of matter can and cannot be changed. They need to know the molecular motion of different states of matter. Those become my 2. For my 4, I ask them to explain certain phenomena that we haven't explicitly address in class. So we've talked about evaporation, but not condensation. We've learned previously why things float or sink, so I ask them to explain why a hot air balloon floats.

Non-science examples: Warning, my knowledge in these other areas kinda sucks so please don't flame me for getting some specific facts or terminology wrong.