One of the things that led me to standards-based assessment is Universal Design for Learning. I believe deeply in multiple avenues of expression. UDL was and is very hard in a traditional grading system. Student A wants to create a presentation, Student B wants to write a poem, Student C wants to make a movie. That's at least 3 different rubrics. Plus, there were inevitably projects that were high on creativity and presentation, while low on content. Every time a student wanted the ability to express himself or herself, it meant a ton of work for me. Plus, every once in a while a student would want to do something so different I really had no idea what I wanted it to look like. The major problem with this system is that rubrics focus on the assignment. What it should focus on is the learning.

Now, I have my topic scales. Everything can be evaluated against that scale.

What knowledge did you demonstrate? Well, it looks like you included the 2.0 standards and partially demonstrated your 3.0 standards. This poem/powerpoint/interpretive dance is a 2.5.

Last year's final was simply,"Demonstrate your knowledge of one of the topics from this year in any way you like." There were a few restrictions for ethical and legal reasons and I required something physically, or digitally, turned in (dances and songs could be recorded). I got a video on the forces involved in archery, a group of girls dancing the different states of matter, an animation on how to solve motion problems, a couple of rap songs, a lot of soccer videos, a couple of photojournals, and yes, even some essays.

One more thing I should point out. My problem with multiple avenues of expression was always that certain methods seemed a little....soft. Instead of having them write an essay, you want me to let them draw a poster? That's not the same thing at all.

Now think about when it's evaluated against your topic scale. How hard would it be to state ALL three Newton's laws and apply them to real life situations in a rap song? There is no soft option because the exact same level of knowledge needs to be demonstrated regardless of how it's done.

Next time you're designing a rubric for an assignment, think about what learning you would like to be communicated. Design your rubric for learning and you'll have something that is not only more flexible, but the focus will be on what has been learned rather than on the assignment itself.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Sunday, January 24, 2010

In defense of skills sheets

In my last post I wrote about why I prefer topics to skills. On Friday, my favorite math teacher very proudly shows me her skill sheet she just created for her pre-algebra class. Because I'm ever-so-subtle, I've been sending her example skills sheets from The Two Dans. (which, coincidentally, is the name of the show NBC is sticking in the Leno timeslot)

I loved the skills sheet.

Last time, I came out in favor of topics. I love me some Big Ideas and I think topics are the best way to do that. Why did I love her skills sheet?

My favorite math teacher created a list of 15 skills that all of her students will need in order to be successful in her class and next year in Algebra. They're core skills. Things like multiplication tables and adding and subtracting fractions. When they get 100% right they put a sticker on a wall chart and they're done with that skill. She's also added a time component. The test is four minutes. Her argument is that these are skills that should be automatic so time is important. Generally, I'm not in favor of time limits because it's introducing a confounding variable but I can see her point and give her the benefit of the doubt on this one.

In this case a topic wouldn't make sense. There really isn't a Big Idea here. It's just a way for her and for her students to keep track of what has been mastered and what needs to be improved. It easily differentiates and students aren't punished if they pass the 15th time instead of the first.

So skills sheets really are just that. A sheet for skills. If you want to connect them to something more meaningful, what David Perkins calls Playing The Whole Game, topics are the way to go.

p.s. - I'm glad she doesn't read this blog. Otherwise, she'd have been pretty pissed at me for pressing her to create a skills sheet for the last two years and then writing a whole post about why I don't like them.

I loved the skills sheet.

Last time, I came out in favor of topics. I love me some Big Ideas and I think topics are the best way to do that. Why did I love her skills sheet?

My favorite math teacher created a list of 15 skills that all of her students will need in order to be successful in her class and next year in Algebra. They're core skills. Things like multiplication tables and adding and subtracting fractions. When they get 100% right they put a sticker on a wall chart and they're done with that skill. She's also added a time component. The test is four minutes. Her argument is that these are skills that should be automatic so time is important. Generally, I'm not in favor of time limits because it's introducing a confounding variable but I can see her point and give her the benefit of the doubt on this one.

In this case a topic wouldn't make sense. There really isn't a Big Idea here. It's just a way for her and for her students to keep track of what has been mastered and what needs to be improved. It easily differentiates and students aren't punished if they pass the 15th time instead of the first.

So skills sheets really are just that. A sheet for skills. If you want to connect them to something more meaningful, what David Perkins calls Playing The Whole Game, topics are the way to go.

p.s. - I'm glad she doesn't read this blog. Otherwise, she'd have been pretty pissed at me for pressing her to create a skills sheet for the last two years and then writing a whole post about why I don't like them.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Dan's concept checklist

If you're semi-conscious in the math blogosphere at all you're aware of dy/dan. (I don't know why I'm providing a link since his traffic is multiple orders of magnitude more than mine.) He's been a long-time advocate of a concept/skills checklist model. Personally, I prefer a topic-based model but that may be based on our subject matters. From what I can tell, here are the differences:

Two quick disclaimers: I've seen this in one form or another in various places so I'm not quite sure what Dan's inspiration was so I can't properly credit it. If I ever happen to run into Dan IRL I'll try to ask. Also, the details are mostly from memory but I think I've captured the spirit.

One more disclaimer: I like the system Dan has developed. I don't want it to seem like I don't. It's a vast improvement over what we normally do.

Dan's concept checklist:

His specific adaptation of the skills checklist breaks his math topics into a whole bunch of skills. There are more than 30. His students take a specific test for each skill, with an easy and hard problem. If they get 100% two times, they pass out of that skill and never have to take it again. His skills checklist was 70% of his grade. I don't know if that's still accurate. He had them track their scores.

My Topic Scores:

After fooling around with all these weird ideas (remind me to tell you about the year I based my grades on Bloom's taxonomy) the baseline for the exact system I use came from this Marzano book. I took my standards and grouped them in to topics based on co-variance. That's a fancy way of saying, "Stuff that is learned together." They get a 0-4 score for each topic, not down to the standard. So far this year we've done Motion, Graphing, Forces, Forces in Fluids, Atoms, Chemical Reactions, and next will be Periodic Table. I have a Scientific Literacy topic all set up but I haven't found the bandwidth in my year to include it yet. There will be 12-15 for the year. I also have them track their scores.

Tracking Forces

The scribd version looks ugly but the big black box is supposed to be a place to bar graph their scores. They put the dates on the right. On the back is a concept checklist and they just traffic light each one. On my tests I have a little letter at the end of each problem that matches to a standard. After we're done checking it they go through a plus/check/minus each one. The number to the left of the standard is the chapter in the book where it can be found.

I have a Word 2003 template if you want me to email it to you. Edit: A link is on the bottom.

Why I prefer topic scores

I prefer the topic scores because it forces connections. This might be a math vs. science thing but I think it helps both me, as the teacher, and my students focus on the larger concepts that link it all. Yeah, you have to learn the vocab and stuff. But keeping it all together helps create a "this is all related" mindset. Even in math, I think separating out is a mistake because of the hierarchical nature. You are losing the "why."

I haven't sat with the math standards long enough to write out an actual topic but I think if I was planning on building a topic it would sound like this in my head:

In my scoring, crazy, insane problem X would be the 3 and subskills would be the 2.

For a 4 a student would need to be able to take what they've learned and apply it in a new way that I haven't taught directly. So take this problem that we've worked on for a flat surface and apply it to a curved surface.

For me, there progress on this scale is 100% of my grade. Nothing else included.

Dan might argue that his skills checklist is simply to ensure his students have mastered the necessary skills to do the complex thing and he assesses that separately. I guess I just don't see the point in having this very nice system that differentiates easily and doesn't punish kids for learning at different rates and then only using it part of the time. A little confused there.

I also am confused about his reasoning for overwriting the previous scores on the tracking sheet I linked to earlier. In the system I use, my students can see a graph of the history of their scores. They can see their growth in a very visual way. They lose that in his tracking system.

Too many students focus on the A (4) or on what their peers have, I don't know how many times I've pointed to a student's graph and said, "Don't worry about being behind your friend. Look at how much you've grown."

Again, back to Disclaimer 2. I like the system. I just think mine fits better for what I'm trying to do. I'm not trying to convert anyone (unless you teach at my school, which is statistically very likely if you're reading this post) but it's nice to know that there are other people out there trying to change the way assessment is done.

Edit: Here's a link to the .dot template. It turns out it's Word 2004 on a mac.

http://www.box.net/shared/6xplu3btfy

Two quick disclaimers: I've seen this in one form or another in various places so I'm not quite sure what Dan's inspiration was so I can't properly credit it. If I ever happen to run into Dan IRL I'll try to ask. Also, the details are mostly from memory but I think I've captured the spirit.

One more disclaimer: I like the system Dan has developed. I don't want it to seem like I don't. It's a vast improvement over what we normally do.

Dan's concept checklist:

His specific adaptation of the skills checklist breaks his math topics into a whole bunch of skills. There are more than 30. His students take a specific test for each skill, with an easy and hard problem. If they get 100% two times, they pass out of that skill and never have to take it again. His skills checklist was 70% of his grade. I don't know if that's still accurate. He had them track their scores.

My Topic Scores:

After fooling around with all these weird ideas (remind me to tell you about the year I based my grades on Bloom's taxonomy) the baseline for the exact system I use came from this Marzano book. I took my standards and grouped them in to topics based on co-variance. That's a fancy way of saying, "Stuff that is learned together." They get a 0-4 score for each topic, not down to the standard. So far this year we've done Motion, Graphing, Forces, Forces in Fluids, Atoms, Chemical Reactions, and next will be Periodic Table. I have a Scientific Literacy topic all set up but I haven't found the bandwidth in my year to include it yet. There will be 12-15 for the year. I also have them track their scores.

Tracking Forces

The scribd version looks ugly but the big black box is supposed to be a place to bar graph their scores. They put the dates on the right. On the back is a concept checklist and they just traffic light each one. On my tests I have a little letter at the end of each problem that matches to a standard. After we're done checking it they go through a plus/check/minus each one. The number to the left of the standard is the chapter in the book where it can be found.

I have a Word 2003 template if you want me to email it to you. Edit: A link is on the bottom.

Why I prefer topic scores

I prefer the topic scores because it forces connections. This might be a math vs. science thing but I think it helps both me, as the teacher, and my students focus on the larger concepts that link it all. Yeah, you have to learn the vocab and stuff. But keeping it all together helps create a "this is all related" mindset. Even in math, I think separating out is a mistake because of the hierarchical nature. You are losing the "why."

I haven't sat with the math standards long enough to write out an actual topic but I think if I was planning on building a topic it would sound like this in my head:

This unit we're going to solve insane problem X. (Could be a word problem, physics problem, area problem, or could be a scary looking math problem that doesn't contain Arabic numbers or letters in our alphabet). That's our goal. What are the skills my kids are going to need to learn in order to solve that problem? That's the subskills.

In my scoring, crazy, insane problem X would be the 3 and subskills would be the 2.

For a 4 a student would need to be able to take what they've learned and apply it in a new way that I haven't taught directly. So take this problem that we've worked on for a flat surface and apply it to a curved surface.

For me, there progress on this scale is 100% of my grade. Nothing else included.

Dan might argue that his skills checklist is simply to ensure his students have mastered the necessary skills to do the complex thing and he assesses that separately. I guess I just don't see the point in having this very nice system that differentiates easily and doesn't punish kids for learning at different rates and then only using it part of the time. A little confused there.

I also am confused about his reasoning for overwriting the previous scores on the tracking sheet I linked to earlier. In the system I use, my students can see a graph of the history of their scores. They can see their growth in a very visual way. They lose that in his tracking system.

Too many students focus on the A (4) or on what their peers have, I don't know how many times I've pointed to a student's graph and said, "Don't worry about being behind your friend. Look at how much you've grown."

Again, back to Disclaimer 2. I like the system. I just think mine fits better for what I'm trying to do. I'm not trying to convert anyone (unless you teach at my school, which is statistically very likely if you're reading this post) but it's nice to know that there are other people out there trying to change the way assessment is done.

Edit: Here's a link to the .dot template. It turns out it's Word 2004 on a mac.

http://www.box.net/shared/6xplu3btfy

Monday, January 18, 2010

Non-academic grades

In my ongoing fight to help reform the grading system at my school one of the big sticking points are the non-academic factors. I'm an advocate of standards-based assessment and in this style you only grade based on the level of achievement on standards or topics. When I bring this up, I always hear three things:

Number 2 boils down to different non-academic factors that teachers value but don't show up on the standards. Organization, neatness, and all that other stuff. Those are perfectly fine to include in their grades but you should separate them out. There always needs to be a chunk (a sizeable one) of your grades that are purely representative of how much the students have learned.

What does that look like? Well for me I'm a science teacher so the topics my students receive grades for this trimester are:

I don't do non-academic grades but if you're big on them, here are some examples:

Why separate?

Ultimately if the purpose of grades are to communicate, you need something to communicate how much the student has actually learned.

Completing work does not mean they've learned. A well-organized binder does not mean they've learned. Behaving in class does not mean they've learned. Does it help? Certainly. But it's just like principal checklists that are used for evaluating teachers. Learning goal posted? Check. Bulletin board organized? Check.

I can do that stuff, but that definitely doesn't mean I'm automatically a good teacher.

The non-academic factors are just indicators, just like those checklists we make fun of. We need to separate out the actual learning a student has achieved.

- Due dates and homework are important because we need to teach responsibility.

- It's not just content I'm teaching, I want them to have skills they'll need for school success.

- (Writing/Reading/Math/etc) are important even though I don't teach it.

Number 2 boils down to different non-academic factors that teachers value but don't show up on the standards. Organization, neatness, and all that other stuff. Those are perfectly fine to include in their grades but you should separate them out. There always needs to be a chunk (a sizeable one) of your grades that are purely representative of how much the students have learned.

What does that look like? Well for me I'm a science teacher so the topics my students receive grades for this trimester are:

- Forces in fluids

- Atoms

- Chemical reactions

- Periodic Table

- Review (I take the main ideas from previous topics and lump them)

I don't do non-academic grades but if you're big on them, here are some examples:

- Work completion

- Organization

- Behavior

- Participation

- Group work

Why separate?

Ultimately if the purpose of grades are to communicate, you need something to communicate how much the student has actually learned.

Completing work does not mean they've learned. A well-organized binder does not mean they've learned. Behaving in class does not mean they've learned. Does it help? Certainly. But it's just like principal checklists that are used for evaluating teachers. Learning goal posted? Check. Bulletin board organized? Check.

I can do that stuff, but that definitely doesn't mean I'm automatically a good teacher.

The non-academic factors are just indicators, just like those checklists we make fun of. We need to separate out the actual learning a student has achieved.

Hinge points part 3

Earlier in the month I wrote a post on hinge points. Turns out Popham actually calls them Choice Points. Mi malo. The feedback I got from it was good, but I often got, "I already do something like that." In talking with my fellow teachers, I realized I didn't make something clear. Choice points are not times when you stare out at your students and see glazed looks and try to fix them. Choice points are designed in and you have designated a threshold ahead of time.

That's the real power. We have a tendency to just go along with our assessment (especially, informal assessment) results. We think accept and move on. Choice points force you to address the issue. I have often done a quick assessment and thought, "This is more confusing than I thought," and then just moved on. I accepted. Not only that, but I hadn't planned ahead of time for how to teach the same concept in a different way. So design them in. Set a threshold. Stick with it.

Again, with Keynote/Powerpoint it's really easy.

That's the real power. We have a tendency to just go along with our assessment (especially, informal assessment) results. We think accept and move on. Choice points force you to address the issue. I have often done a quick assessment and thought, "This is more confusing than I thought," and then just moved on. I accepted. Not only that, but I hadn't planned ahead of time for how to teach the same concept in a different way. So design them in. Set a threshold. Stick with it.

Again, with Keynote/Powerpoint it's really easy.

- Me talking and showing stuff.

- Multiple choice slide.

- Quick mental math.

- Move on to the next slide or skip ahead.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

That's too hard to measure!

I often get caught up in arguments with my peers about evaluation. We'll start talking about ways of going beyond right/wrong or complete/not complete and get in to what is the true purpose of whatever they're teaching. Inevitably, one of my fellow teachers will say something like, "Well, you can't really measure that."

In science, we really do think of it as reducing uncertainty. I'm comfortable with designing a measurement system that only reduces uncertainty. The level of uncertainty that I'm ok with depends on the magnitude of the decision.

Example:

How do I measure how engaged a student is in the lesson?

I remember reading a book on Japanese Lesson Study and it said that the teachers actually counted "shining eyes" as a way to tell if students were engaged and interested in the lesson. You might argue that counting shining eyes seems fuzzy or that it doesn't offer complete information. That might be true, but what is also true is that you now have more information than when you started. You have reduced your uncertainty.

If you combine this measurement with other ones you can start getting a pretty good idea of how engaged your students actually were.

Here are a few things I say might occur if students are more engaged in a lesson:

1. Ask questions

2. Less bathroom requests

3. Asking for more time

4. Number of people participating

5. Less disruptions

6. Keep going even after they're technically completed

7. Asked for resources to continue at home

If I just measure a few of those, I can begin to get a very good, less uncertain, idea of the level of engagement in my class.

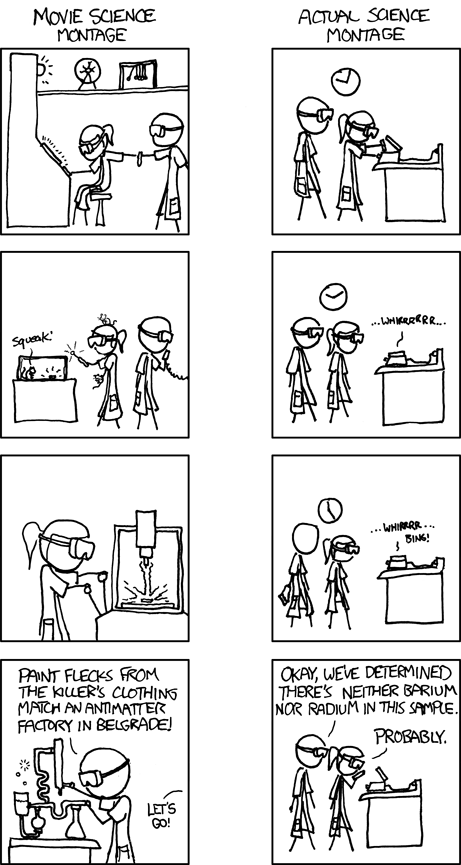

Obligatory XKCD link:

It's anticlimactic compared to the movie version but those scientists know a little bit more than they did before.

I was flipping through the book How To Measure Anything by Douglas Hubbard and came across this definition of measurement:

Measurement: A set of observations that reduce uncertainty where the result is expressed as a quantity.After reading this quote, I realized I had fallen victim to the Curse of Knowledge. Seeing it written out in a book made me realize that not everyone thought this way. Many (most?) people tend to think of measurements as something very exact. That tree is 12 feet and 3 inches tall. I weigh 181.2 pounds.

In science, we really do think of it as reducing uncertainty. I'm comfortable with designing a measurement system that only reduces uncertainty. The level of uncertainty that I'm ok with depends on the magnitude of the decision.

Example:

How do I measure how engaged a student is in the lesson?

I remember reading a book on Japanese Lesson Study and it said that the teachers actually counted "shining eyes" as a way to tell if students were engaged and interested in the lesson. You might argue that counting shining eyes seems fuzzy or that it doesn't offer complete information. That might be true, but what is also true is that you now have more information than when you started. You have reduced your uncertainty.

If you combine this measurement with other ones you can start getting a pretty good idea of how engaged your students actually were.

Here are a few things I say might occur if students are more engaged in a lesson:

1. Ask questions

2. Less bathroom requests

3. Asking for more time

4. Number of people participating

5. Less disruptions

6. Keep going even after they're technically completed

7. Asked for resources to continue at home

If I just measure a few of those, I can begin to get a very good, less uncertain, idea of the level of engagement in my class.

Obligatory XKCD link:

Saturday, January 9, 2010

Hinge points and index cards

In my last post I wrote about hinge points. Kate has just posted a way she uses index cards in lieu of clickers in her class. The only thing I would change is putting each set on a binder ring. Just seems easier to keep them together.

Now all you need to do is design in a hinge point question. Decide what percentage of students need to get this question right. Calculate the correct responses and you now know whether to move on or try again.

Now all you need to do is design in a hinge point question. Decide what percentage of students need to get this question right. Calculate the correct responses and you now know whether to move on or try again.

Monday, January 4, 2010

Does everyone get it now?

Traditionally, when I'd finish up on a lecture, a unit, a something, I'd address the class with a generic question like, "Are there any other questions?" or "Anybody still need help?"

Here's the thing. I'm not actually asking those questions and waiting for an answer. My students and I have entered into an implicit agreement that when I ask a question like that, silence is the only correct response. If they're silent, I get to move on and they get to see something new. Clearly, it works out for everyone.

Unless by "works out" you mean "students actually learn something." If that's the case, my traditional method sucks.

Ignore the fact that students don't like revealing their ignorance to their peers, especially as teenagers. Also, ignore the fact that my question is so broad that clearly everyone should have a question about something. The real problem is that I waited all the way until the end of whatever I'm doing to figure out if my students know what's going on.

The old me would just teach through and try to fix the problem at the end of the assembly line. The new me designs in hinge points (edit: Ok, they're actually called Choice Points, which is an excellent blog name btw).

The term hinge points is used in a number of ways in education. John Hattie in Visible Learning uses that term to specify at what point an educational innovation would have a discernible affect of educational outcomes. For his purposes, an effect size of d = 0.4 is his hinge point.

I'm referring to hinge points as it refers to formative assessment. I first came across this idea in an article by James Popham. I only have a dead tree version so I'll point you to a pretty interesting book by him that also mentions them.

Pretend you're driving somewhere, perhaps to school. You have two routes you can go. You get to the intersection and each day, depending on the traffic, you decide whether to turn left or right. This is what hinge points are. They're stopping points you design into your day/week/month/year. You perform an assessment and the results determine the route you take next.

We are all familiar with reteaching after everyone bombs a test. By designing hinge points in to your day you can avoid that. Instead of fixing problems at the end of the assembly line, you're fixing as you go.

I think we're all familiar with adjusting the instruction the next day based on exit slips or the results of in class practice. That's pretty easy.

What about hinge points in the middle of class? This is a little tougher but something I've been working on.

Let's say I'm teaching a new concept in class, like the structure of atoms. The first twenty minutes of class we've been working on the idea that most of the mass is located in the nucleus. Ahead of time, I've designed in a question to determine how well my students understand that idea. I've also pre-determined what percentage of the class needs to get it right for me to move on. That percentage depends on the importance of the concept for learning whatever is next. If you're outta luck without it, then I might decide 80% of the class needs to get the question right. If you can muddle through and the next concept might help you understand the first, I might say only 20% need to get it.

In this case, because it's pretty early I'm only looking for surface understanding. So I put up a multiple choice question that says something like, "Which action would change the mass of an atom the most?"

Using whatever response system you prefer, determine the percent of the class that got it right.

In the world of Keynote/Powerpoint you can easily change up what happens next. You can either go to slide 10 and try to reteach this idea in a different way or skip to slide 20 and continue on to whatever is next. Of course if you're feeling saucy you can plan separate activities depending on the results.

You're making adjustments as you go. Going back to the driving analogy. Our old way of teaching is like getting directions and following them regardless of where it takes you when you're driving. When the directions are finished, then you figure out where you are and make corrections. Now, you're constantly making adjustments based on what's happening as you drive.

Three key points to remember:

1. Design them in.

2. Decide ahead of time what percentage of the class needs to get it for you to move on.

3. Try to use hinge points during class, not just between classes.

Here's the thing. I'm not actually asking those questions and waiting for an answer. My students and I have entered into an implicit agreement that when I ask a question like that, silence is the only correct response. If they're silent, I get to move on and they get to see something new. Clearly, it works out for everyone.

Unless by "works out" you mean "students actually learn something." If that's the case, my traditional method sucks.

Ignore the fact that students don't like revealing their ignorance to their peers, especially as teenagers. Also, ignore the fact that my question is so broad that clearly everyone should have a question about something. The real problem is that I waited all the way until the end of whatever I'm doing to figure out if my students know what's going on.

The old me would just teach through and try to fix the problem at the end of the assembly line. The new me designs in hinge points (edit: Ok, they're actually called Choice Points, which is an excellent blog name btw).

The term hinge points is used in a number of ways in education. John Hattie in Visible Learning uses that term to specify at what point an educational innovation would have a discernible affect of educational outcomes. For his purposes, an effect size of d = 0.4 is his hinge point.

I'm referring to hinge points as it refers to formative assessment. I first came across this idea in an article by James Popham. I only have a dead tree version so I'll point you to a pretty interesting book by him that also mentions them.

Pretend you're driving somewhere, perhaps to school. You have two routes you can go. You get to the intersection and each day, depending on the traffic, you decide whether to turn left or right. This is what hinge points are. They're stopping points you design into your day/week/month/year. You perform an assessment and the results determine the route you take next.

We are all familiar with reteaching after everyone bombs a test. By designing hinge points in to your day you can avoid that. Instead of fixing problems at the end of the assembly line, you're fixing as you go.

I think we're all familiar with adjusting the instruction the next day based on exit slips or the results of in class practice. That's pretty easy.

What about hinge points in the middle of class? This is a little tougher but something I've been working on.

Let's say I'm teaching a new concept in class, like the structure of atoms. The first twenty minutes of class we've been working on the idea that most of the mass is located in the nucleus. Ahead of time, I've designed in a question to determine how well my students understand that idea. I've also pre-determined what percentage of the class needs to get it right for me to move on. That percentage depends on the importance of the concept for learning whatever is next. If you're outta luck without it, then I might decide 80% of the class needs to get the question right. If you can muddle through and the next concept might help you understand the first, I might say only 20% need to get it.

In this case, because it's pretty early I'm only looking for surface understanding. So I put up a multiple choice question that says something like, "Which action would change the mass of an atom the most?"

Using whatever response system you prefer, determine the percent of the class that got it right.

In the world of Keynote/Powerpoint you can easily change up what happens next. You can either go to slide 10 and try to reteach this idea in a different way or skip to slide 20 and continue on to whatever is next. Of course if you're feeling saucy you can plan separate activities depending on the results.

You're making adjustments as you go. Going back to the driving analogy. Our old way of teaching is like getting directions and following them regardless of where it takes you when you're driving. When the directions are finished, then you figure out where you are and make corrections. Now, you're constantly making adjustments based on what's happening as you drive.

Three key points to remember:

1. Design them in.

2. Decide ahead of time what percentage of the class needs to get it for you to move on.

3. Try to use hinge points during class, not just between classes.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)