Remember when you were young and you'd get into an argument with your parents? I was a, let's say, special child in that regard. Eventually one or both of my parents would run out of reasons for doing something and resort to the "because I say so" argument. I have a vague recollection from Philosophy 10 that this is called

argument from authority.

Points are our ultimate "because I say so." How many times have you as a student or teacher had this conversation:

Student: Why should I do this?

Teacher: Because it's worth X points.

When we don't do the work required to link our assignments with clear learning goals this is what we fall back on.

The key then to getting your students to complete their assignments is to create a clear link between "doing the work" and learning what you need to learn. Your new conversation should be:

Student: Why should I do this?

Teacher: Because it will help you learn X.

This is obviously a constant and ongoing conversation. I've mentioned it before in an older

post but it's one of the crucial mindset shifts that needs to occur for your students to really buy in. You need to make their learning progress clear and relate it to the effort they've put in. Your classroom language is crucial here, which I'll post about in the future.

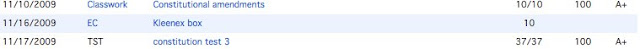

Here's one example I show my kids to help them link the work with the learning. I take a survey every trimester (I show last year's results in the beginning of the year). There are two questions:

- Think of everything you were asked to do in science this trimester, what percentage do you think you completed?

- What was your final trimester grade?

When I say everything I mean everything. I tell them to count exit slips, notes, turn to your partner types of activities, warm-ups, etc.,in addition to the traditional worksheets/lab stuff. I throw the results up on the screen the next day:

I remind them that I don't give them points for turning in work. What's going on in the graph is the students who are doing more work are learning more. I should probably print this graph out so I can just point to it every time the above conversation happens but paper has become quite the precious commodity at my school.

As a side note this is a good opportunity to do a mini-lesson on problems with self-report surveys. Generally, the A students tend to under-report how much work they've actually done. Some of them do it because they like to pretend they understood everything easily. Others don't count things like coming after school or getting help from friends during lunch. So while they may have only done 50% of everything in class, they more than made up for it with the extra time they spent outside of class that they don't think counts as work.

The F student results are also skewed because the super-duper F students don't even turn in the survey. I've done this survey 7 times now and every time it ends up similar to that pattern above with A students doing the most, a nice even tapering by grade, and a huge drop off to F.