For our school book club we're reading Drive. Note to colleagues: Book discussion is Tuesday. Bring an appetizer.

Just quickly, I can't say I was in love with Drive. It didn't include anything particularly groundbreaking. I'd find myself breezing through pages thinking I've read that before. I don't know how many times I can read about 20% time or the invention of the Post-it. That being said there are a couple of things that are stuck in my head.

Fedex days: In the book, Dan Pink mentions a company called Atlassian. They have Fedex days. The premise of these is that you have 1.5 to deliver something. It can be anything product related and has to be out of your normal work responsibilities. I LOVE this idea for schools. I don't know how many useless PD sessions I've sat through just clocking time. What if instead our administrators got us together in the morning and said, "Come back at 3pm with something to make our school better." I imagine it could be an unconference setup where there's a big whiteboard and we rush up with our ideas or sign on to ones we're interested in. It'd have to be something out of our normal day to day so nothing like, "Our school will be better if I catch up on my grading and finish hanging posters in my room." We go out with our teams and come back with something. We do our pitch and listen to others. I'm not actually sure how Atlassian decides what to pursue further but I imagine there are ideas that just grab people. I'm getting excited just typing this.

Schools as businesses:

Nancy Flanagan has a very insightful post on the "run schools like a business" premise. Read it first. I'll wait......

B Corporations: Nancy Flanagan quotes Roxanna Elden who says that "test scores are the product." Our profit is measured by test scores. That unrelenting drive to increase test scores has led to schools behaving like businesses: rampant cheating by all, sacrificing long-term values for short-term gains, and treating innovation like intellectual property. On the other hand, I'm not with the totally-anti-fight-the-world-all-testing-is-bad crowd. One thing testing has done is helped uncover those groups we let slip by. One of the high performing schools near me has a 90% proficiency rate. It's in an affluent area that is attended by kids who have parents that are professors at one the best universities in the entire world. However, less than a quarter of their Hispanic population is proficient. Pre-testing, they would ignored those kids. Now, they have to address it.

Also, testing exists. I don't think it's going away and I don't think it's productive to ignore or fully resist. This is where the B Corp idea comes in. A B Corp has a primary responsibility not to shareholders, but to stakeholders. Profit, while good, is not the primary driver. You must consider your employees, the environment, and the community. Schools can and should be the same way. Our profit (test scores) should be considered. We should try to raise them. However, it shouldn't be our primary motive. We should be able to consider the needs of our students, teachers, and the community FIRST while at the same time raising test scores. They don't need to be mutually exclusive. We must address the needs of our stakeholders while delivering a profit.

Anyone else who read Drive, I'd love to hear what you thought. If you're not at my school, you can leave a comment and I can bring it in and share it on Tuesday.

Addendum: I've been obsessing about the FedEx days and have decided to pitch it to my school for our next PD. What I'd like is some ideas to help them understand what might be done. I'm also wondering about structure. I think an unconference format would probably be too inefficient given that we'd only have from 8-3. At the two corporations I've worked for we had a Digg-like system for posting ideas, commenting on them, and voting them up or down. Perhaps something like that ahead of time would be better.

I think my school actually might go for it. Not so much because it might be great, but because they wouldn't have to pay for a speaker and because they can always blame me if it doesn't work. "That was just another of Jason's crazy ideas."

What would you deliver? What structures or guidelines would you have in place? Comment or twitter.

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Thursday, February 25, 2010

My love affair with topic scales continues

We are 11 school days from the end of the trimester. For as much as I talk about intrinsic motivation, I fully admit that I love when my students realize the end is near and they finally get going.

As students are walking in I have this projected onto the whiteboard (I project right onto the whiteboard so I can draw on it):

As students are walking in I have this projected onto the whiteboard (I project right onto the whiteboard so I can draw on it):

They grab their portfolios, check their tracking sheet for the periodic table, and sort themselves out.1 There are a couple of options at each table along with green, yellow, and red cups to let me know who needs attention. I spend about two minutes at each table to clear up any confusion or problem and spend the rest of the period skittering around the class like a crab. Good times.

This is certainly possible without topic scales. But self-evaluation and self-tracking makes this so much easier.

1: I still have to send three or four kids per class to different spots because they want to sit with their friends instead of work on their weaknesses. I would blame it on being 8th graders, but really I would have done that from K to college. In fact, I still do that at every PD session we have in my district.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

With apologies to Jessica Hagy

Indexed.

I'm in the midst of a wonderful February break and I've devoted at least two full days to planning and preparing stuff. At one point I sat there and wondered, "When is this supposed to get easier?" I remember my first year I'd be up all night planning and scraping through every day. Now? I'm still up all night planning. It's not that panicky, "Oh crap, I don't know what I'm doing tomorrow," kind of planning anymore, but I also don't feel like I'm saving any time. It took me a second to figure it out and since it's assessment-related, it ends up with a blog post.

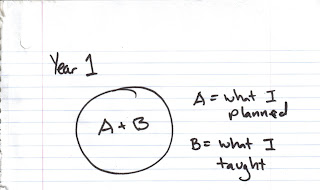

Here's a drawing of the relationship between what I planned to teach and what I actually taught in my first year. Sorry for the messy handwriting. Now you know why I don't teach first grade.

Everything that I planned got taught. I was like a train going down a track.

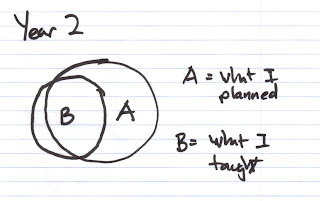

Year two went something like this:

I understood that problems arose so I planned for a little more. There would be stuff I wouldn't use that were just-in-case things. I'd have to improvise a little when an interesting question came up or we got stuck in a place I didn't anticipate.

Now it's more like this:

A ton of planning still. But each period tends to get a better target of what they need. I use more formal and informal choice points. I actually use my assessment results to guide my teaching (a future "I"m already doing that" post). In general the first day of a unit starts off fairly similar and then each day starts to diverge. We start to converge again towards the end but usually don't hit the end mark on the exact same day.

What does the future hold?

I wasn't interested in drawing 140 different circles but clearly the more I can individualize the better. I also want to move away from, "I plan. You do." I'm trying to move towards, "Let's create a plan together." With hopefully the final goal of, "Here's your goal, create a plan to get there."

Final note:

This is actually one of the things that really scares the teachers at my school. The ideas that:

I'm in the midst of a wonderful February break and I've devoted at least two full days to planning and preparing stuff. At one point I sat there and wondered, "When is this supposed to get easier?" I remember my first year I'd be up all night planning and scraping through every day. Now? I'm still up all night planning. It's not that panicky, "Oh crap, I don't know what I'm doing tomorrow," kind of planning anymore, but I also don't feel like I'm saving any time. It took me a second to figure it out and since it's assessment-related, it ends up with a blog post.

Here's a drawing of the relationship between what I planned to teach and what I actually taught in my first year. Sorry for the messy handwriting. Now you know why I don't teach first grade.

Everything that I planned got taught. I was like a train going down a track.

Year two went something like this:

I understood that problems arose so I planned for a little more. There would be stuff I wouldn't use that were just-in-case things. I'd have to improvise a little when an interesting question came up or we got stuck in a place I didn't anticipate.

Now it's more like this:

A ton of planning still. But each period tends to get a better target of what they need. I use more formal and informal choice points. I actually use my assessment results to guide my teaching (a future "I"m already doing that" post). In general the first day of a unit starts off fairly similar and then each day starts to diverge. We start to converge again towards the end but usually don't hit the end mark on the exact same day.

What does the future hold?

I wasn't interested in drawing 140 different circles but clearly the more I can individualize the better. I also want to move away from, "I plan. You do." I'm trying to move towards, "Let's create a plan together." With hopefully the final goal of, "Here's your goal, create a plan to get there."

Final note:

This is actually one of the things that really scares the teachers at my school. The ideas that:

- Each period might not be doing the same thing on the same day.

- Each student might not be doing the same thing on the same day.

- You might not know what you're doing on Thursday until you see how Wednesday goes.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Are you sure that's what you really want?

As Matt Townsley has posted, homework is always one of the huge sticking points when it comes to standards-based grading. Inevitably, a teacher will always turn to me and say, "Well if they're not going to get points for homework, how am I going to hold them accountable?"*

I think Matt has already covered that topic pretty well so I won't get into the day-to-day of it. I've touched on it once before. What I wanted to blog about was the last part of the question, "hold them accountable."

Is that what we really want? We want to hold our kids accountable? Take a second and think about the implications of that word. The word accountable does two things. It assigns blame. And it shifts the focus. Not only that, but we have to hold them to it. I have this mental image of us getting kids into a sleeper hold while someone from the Electric Company zaps them.

We don't really want to hold our kids accountable. What we want is responsibility. Responsibility doesn't assign blame. We hold our kids accountable. We share responsibility.

In the book Drive, Daniel Pink mentions that Robert Reich goes into businesses and counts pronouns. How many times are employees using "we" versus "you"? Healthy companies say "we."

In our schools, how often are we "holding kids accountable" and how often are we "sharing responsibility"?

*In my particularly snarky moods I tend to respond with, "I agree they should be held accountable, just like NCLB holds us accountable." If you really want to get a teacher to shiver, equate our practices with NCLB.

I think Matt has already covered that topic pretty well so I won't get into the day-to-day of it. I've touched on it once before. What I wanted to blog about was the last part of the question, "hold them accountable."

Is that what we really want? We want to hold our kids accountable? Take a second and think about the implications of that word. The word accountable does two things. It assigns blame. And it shifts the focus. Not only that, but we have to hold them to it. I have this mental image of us getting kids into a sleeper hold while someone from the Electric Company zaps them.

We don't really want to hold our kids accountable. What we want is responsibility. Responsibility doesn't assign blame. We hold our kids accountable. We share responsibility.

In the book Drive, Daniel Pink mentions that Robert Reich goes into businesses and counts pronouns. How many times are employees using "we" versus "you"? Healthy companies say "we."

In our schools, how often are we "holding kids accountable" and how often are we "sharing responsibility"?

*In my particularly snarky moods I tend to respond with, "I agree they should be held accountable, just like NCLB holds us accountable." If you really want to get a teacher to shiver, equate our practices with NCLB.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

I'm already doing that. Part 1

When I first started really examining my assessment practices, I'd often read a practice or strategy and think, "I'm already doing that," and just skip ahead. Turns out, I wasn't already doing that. I was doing something only nominally related to what I should have been doing. This series is dedicated to the former me that felt like I was "already doing that."

Advice: You need to teach the standards.

Me: I'm already doing that.

<<

Begin brief interjection

Ok....I understand the anti-standards argument. Trust me. I get it. However, at least in my district and I'm assuming in my state, teaching the standards is your job. It's not optional. You can't just choose to ignore them. How you want to teach them is up to you (within reason). But if your kids aren't learning the standards, you're not doing your job.

End interjection

>>

It turns out I wasn't already doing that. I'm a science teacher. Science teachers are probably more guilty than other teachers of being a little.....off. We like to blow stuff up. We like to see stuff blow up. We like it when things sparkle and flame and glow and give off terrible odors. We really love when our experiments are loud enough to bother other classes. If we set off a fire alarm, we're secretly proud of ourselves.

I thought I was teaching the standards. I wasn't.

What I was doing was gathering a long series of really, really fun experiments and demos. Afterwards, I'd fit them to my standards. Build a bridge? Umm...forces! Trebuchet? That involves velocity. Gummi bear sacrifice? I think that has to do with...the periodic table....somehow.

I wasn't teaching the standards. I was fitting them in where they were convenient.

Sounds fun right? It was. But this way is also inherently lazy. Turns out if I started with the standards, I could still find the fun stuff and satisfy my inner pyro. Sometimes it just took me longer to find or develop something for that specific standard.

I also had a ton of fat in my curriculum. I had to squish in the stuff I was supposed to teach around the stuff I wanted to teach. I was always behind.

Now? I'm like a laser. Do I occasionally take a little wander to satisfy my inner pyro? Sure. But I've cut enough fat I'm not sacrificing what I'm supposed to be teaching. I also don't delude myself into thinking that building a blinking LED circuit is anywhere on the California 8th grade science standards.

Next time you feel yourself reading a book or at a training and you catch yourself thinking, "I'm already doing that," instead of shutting down, take a second and try to figure out if you really are actually doing that.

Advice: You need to teach the standards.

Me: I'm already doing that.

<<

Begin brief interjection

Ok....I understand the anti-standards argument. Trust me. I get it. However, at least in my district and I'm assuming in my state, teaching the standards is your job. It's not optional. You can't just choose to ignore them. How you want to teach them is up to you (within reason). But if your kids aren't learning the standards, you're not doing your job.

End interjection

>>

It turns out I wasn't already doing that. I'm a science teacher. Science teachers are probably more guilty than other teachers of being a little.....off. We like to blow stuff up. We like to see stuff blow up. We like it when things sparkle and flame and glow and give off terrible odors. We really love when our experiments are loud enough to bother other classes. If we set off a fire alarm, we're secretly proud of ourselves.

I thought I was teaching the standards. I wasn't.

What I was doing was gathering a long series of really, really fun experiments and demos. Afterwards, I'd fit them to my standards. Build a bridge? Umm...forces! Trebuchet? That involves velocity. Gummi bear sacrifice? I think that has to do with...the periodic table....somehow.

I wasn't teaching the standards. I was fitting them in where they were convenient.

Sounds fun right? It was. But this way is also inherently lazy. Turns out if I started with the standards, I could still find the fun stuff and satisfy my inner pyro. Sometimes it just took me longer to find or develop something for that specific standard.

I also had a ton of fat in my curriculum. I had to squish in the stuff I was supposed to teach around the stuff I wanted to teach. I was always behind.

Now? I'm like a laser. Do I occasionally take a little wander to satisfy my inner pyro? Sure. But I've cut enough fat I'm not sacrificing what I'm supposed to be teaching. I also don't delude myself into thinking that building a blinking LED circuit is anywhere on the California 8th grade science standards.

Next time you feel yourself reading a book or at a training and you catch yourself thinking, "I'm already doing that," instead of shutting down, take a second and try to figure out if you really are actually doing that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)